BMI, or the body mass indicator, is a common metric used to measure health. Learn where it came from and why it’s incredibly problematic and misleading—and what to focus on instead when considering health.

What is BMI?

Whenever you head in for a check up, there is a round of routine checks and stats that the doctor will go through. And one of them is the BMI. From my own personal experience and from what I know from research, this is one of the most misused metrics of health and it can often make us think there’s a problem when there really isn’t.

I wanted to share information on it—what it is, where it came from, how it’s used (and how usage has changed in problematic ways) to give you more context for what you might here at a check up. And to offer ideas on what to ask as follow ups, and how to think about health in a broader context.

According to the CDC:

Body mass index (BMI) is a person’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. BMI is an inexpensive and easy screening method for weight category—underweight, healthy weight, overweight, and obesity.

It’s an inexpensive, easy tool that is not intended to diagnose the health of a person, but it is often used that way—which is problematic for many reasons.

Table of Contents

Meet Unapologetic Eating

Alissa Rumsey, MS, RD is the author of the new book, Unapologetic Eating: Make Peace with Food and Transform Your Life. It’s quickly become one of my favorite books that looks at the intersection of diet culture, nutrition, self-care, and the power of respecting your own body.

ORDER IT: Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Indiebound.org, or Book Depository

Alissa’s thorough explanations of BMI particularly jumped out at me because I know just how often those numbers are used at checkups in ways they were never intended to be used.

We hear that our kid is in the 95% or 5% and immediately think they need to gain or lose weight. But that’s not true.

Below is an excerpt on the origins of the BMI chart, how it’s being misused, and what to know when you hear the numbers at a checkup.

Excerpted from Unapologetic Eating: Make Peace with Food and Transform Your LifeCopyright © 2021 by Alissa Rumsey. Published February 2021 by Victory Belt Publishing

Why the BMI Is BS

The BMI calculation uses a person’s height and weight to categorize them as underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese, or morbidly obese. This measurement has become the de facto way that government agencies, medical professionals, drug manufacturers, and health researchers classify people’s weight to evaluate, and even diagnose, health. Yet the BMI has been widely recognized as a problematic measurement for several reasons:

It’s based on height and weight data primarily from white, middle- to upper-class Europeans, which means it’s not a representative sample of the general population and does not account for differences in “average” body sizes in other ethnic groups.19

It does not take into consideration differences in age, sex, bone structure, body fat versus muscle, fat distribution, or how muscle mass changes with age. For example, people who have a high percentage of muscle mass end up being classified as “overweight” or “obese,” even if they have low amounts of body fat.

The differences between BMI classifications—i.e., between “normal” weight and “overweight” or “obese”—are largely arbitrary.20 They are not based upon any scientific data but defined instead by a handful of people with ideas of what a “normal” weight should be.

In 1998, the National Institutes of Health, in a controversial move, adjusted the cut off for “overweight” down to 25.21 So 37 million Americans went to bed having a “normal” BMI and woke up the next day considered to be “overweight.” (Read more about this in the next section.)

BMI isn’t a good indicator of health status. A 2016 study of more than 40,000 people found that 47 percent of people classified as “overweight” and 29 percent classified as “obese” were metabolically healthy (meaning that their blood pressure, cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, and C-reactive protein [a measure of inflammation] were all normal). Plus, 30 percent of people who were in the “normal” weight BMI category were found to be metabolically unhealthy.22

Let’s dig deeper into a few of these points.

BMI Categories Are Largely Arbitrary

In 1998, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) decided to lower the “overweight” BMI category threshold to 25 for all genders. Previously, it had been 28 for men and 27 for women.23 The committee based this decision on a World Health Organization (WHO) report from 1996, which was written by the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF), which recommended the BMI category of “overweight” be lowered.

The primary funders of the IOTF report? Hoffmann-La Roche and Abbott Laboratories, two pharmaceutical companies that make weight-loss drugs. Not to mention that various weight-loss drug companies were paying many of the researchers and scientists who were on the WHO and NIH committees.

These companies had an active interest in having more Americans classified as “overweight” so that they would have a much larger market for their weight-loss drugs.

The “Obesity” Paradox

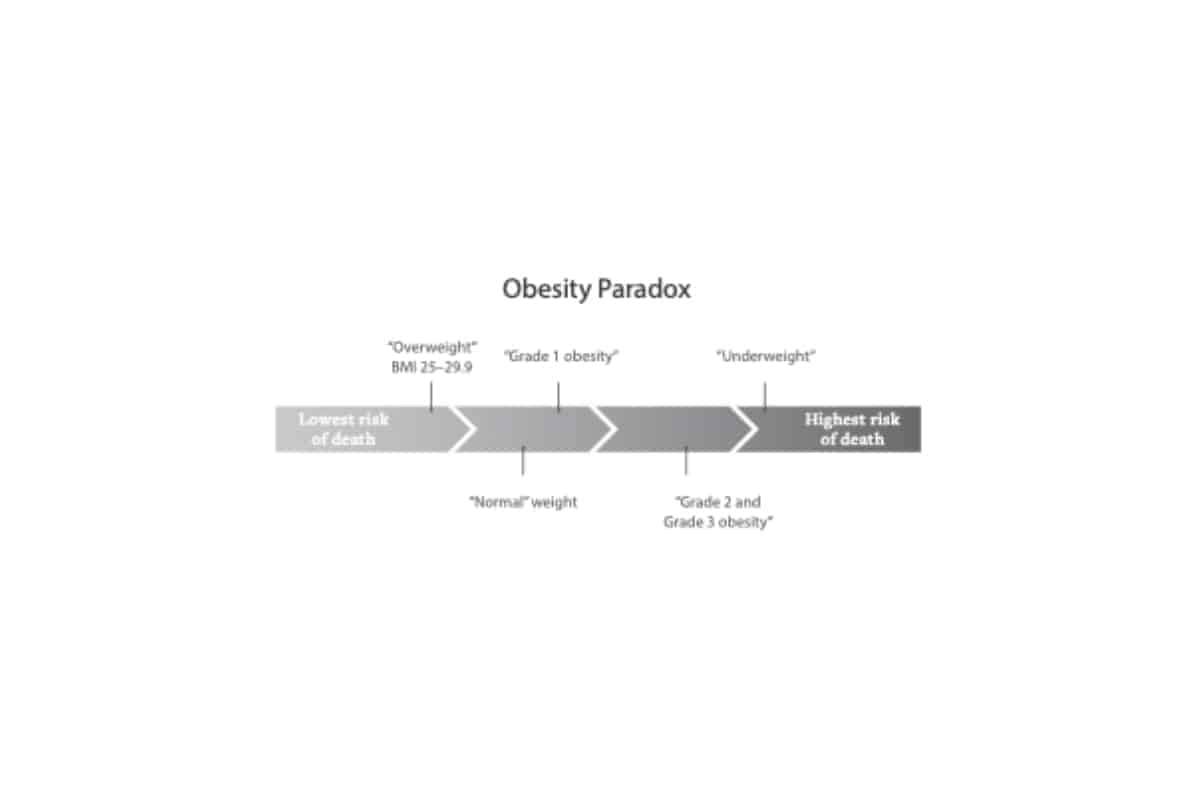

More evidence to support that BMI is BS: The BMI category with the highest risk of death is actually people who are classified as underweight. In fact, if you’re “underweight,” you are twice as likely to die than someone in the “normal” weight category.

Not only that, but the BMI category with the lowest risk of death is people who have a BMI of 25 to 29.9 and are classified as “overweight.” Known as the obesity paradox, people who are “overweight” live the longest out of any group, including people who are “normal” weight.

Meanwhile, people who have a BMI between 30 and 34.9 (in the “obese” range) have the same risk of death as a person with a “normal” BMI.24 (Side note: It’s considered a “paradox” only because researchers, with their weight bias, expected the opposite to be true.) The following illustration shows least risk of death to greatest risk of death based on BMI.

If people who are “underweight” have the highest risk of mortality, why is it that people rarely accuse models or other thin people of “promoting death”? Yet fat people are constantly trolled for this exact thing and are forced to “prove” their healthfulness. Oh right: fatphobia (aka, not health).

In addition to conferring a lower risk of death, a higher BMI also appears to be beneficial in many instances. For example, in people with type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease, those who have a BMI in the “obese” range live longer than thinner people with the same conditions.

A high BMI also seems to have some protective effect as we age, with research finding that in people older than age 55, those with a BMI in the “overweight” and “obese” categories had decreased risk of death compared to people with “normal” and “underweight” BMIs.25

The BMI Misclassifies Large Swaths

of the Population

Some doctors find BMI useful as a screening tool to indicate when to check people for things like high cholesterol or elevated blood pressure. Although this may be helpful in certain cases, the BMI is not a perfect measure given that 30 percent of people with a “normal” BMI have health conditions like diabetes or high cholesterol.26

Also, having a higher BMI doesn’t automatically mean a person is in poor health (like my client who was perfectly healthy but was told to get weight-loss surgery based only on her BMI). Although a higher BMI may be associated with health risks in certain people, it does not mean that a high BMI itself is a health state.

A great example of this can be found in professional athletes: Due in large part to their high muscle mass, many pro football players have BMIs of 30 or greater, putting them in the “obese” category, even if they are healthy.

This mismatch isn’t just in athletes: Research has found that almost 50 percent of people who are in the “overweight” BMI category and 30 percent of people with an “obese” BMI are actually healthy, showing no signs of disease.27

The BMI was never meant to be used as a proxy for health, yet it is now used as exactly that when people visit their doctor’s office, when scientists conduct research studies, and when the government makes policies at the population level.

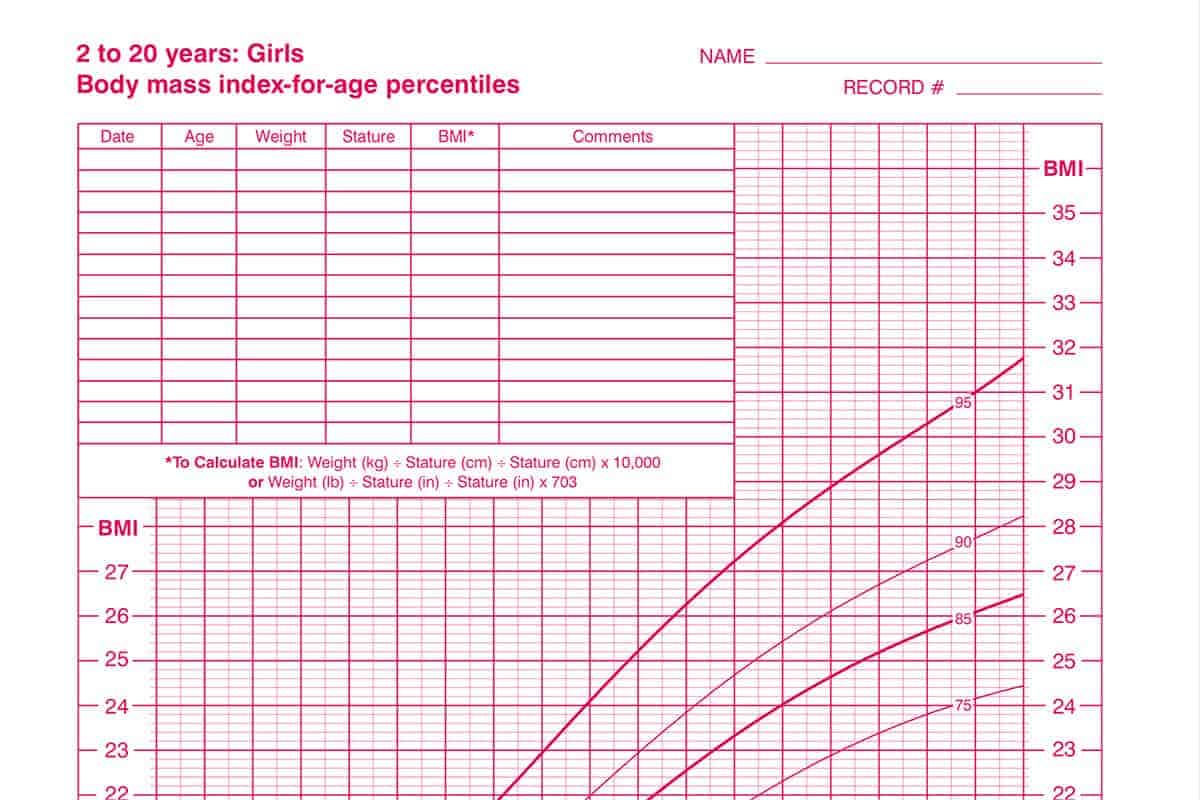

BMI and Kids

I find all of that information to be incredibly helpful in thinking through metrics that we get from the pediatrician. And also, when it comes to BMI and kids specifically, the CDC says:

These percentiles were determined using representative data of the U.S. population of 2- to 19-year-olds that was collected in various surveys from 1963-65 to 1988-94.

Which means that our kids are NOT being compared to their peers. They’re being compared to kids decades ago.

Our bodies have been getting larger over the decades, but that could be from a whole host of reasons—and using charts to (however unintentionally) shame families about body size is completely unhelpful.

Further Reading

- For more on what to do if your child is considered “overweight” or if a medical professional suggests they need to lose weight, read more about Why Kids Don’t Need to Diet—and learn what to do instead.

- Here are some tips on fostering body positivity.

- These tips on how to appreciate your own body can be so helpful too.

- I also love the books The Eating Instinct, What We Don’t Talk about When We Talk About Fat, and Intuitive Eating for more of the big picture context on all of this.